The aftermath of the financial crisis

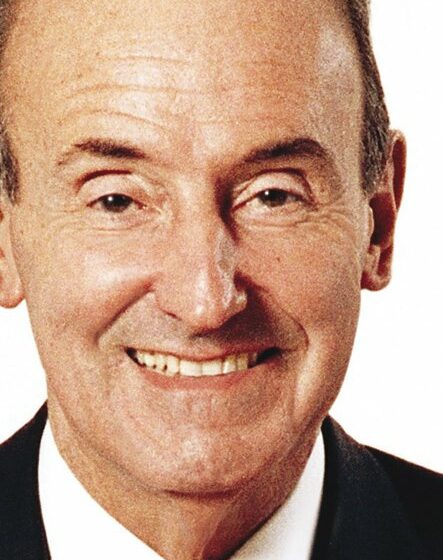

The US Government has responded to the financial crisis with significantly increased supervision, regulation and enforcement, says Rodgin Cohen of Sullivan & Cromwell

El Gobierno y las agencias financieras de los Estados Unidos han reaccionado a la crisis con un incremento en el control y la regulación, pero esto es solo el principio, opina Rodgin Cohen, Presidente de Sullivan & Cromwell. Hace dos años, el sistema financiero mundial estaba al borde del colapso, y solo fuimos capaces de salir del abismo a través de una intervención masiva del Estado, además de una gran cantidad de suerte, afirma.

Two years ago the financial world was on the edge of an abyss. We were experiencing actual “contagion” as the entire financial system froze. We were only able to step away from the edge through massive, and in the US politically unpopular, Government intervention and a very large measure of luck. And we remain in a period of economic contraction. A crisis of such magnitude demands thorough and comprehensive analysis, with the objective to reduce the potential that it may be repeated and to minimise the impact if it does.

The US Government response to the crisis largely reflected its key causes. The most obvious was that institutions took on too much risk for which their management processes proved inadequate. There were also too many gaps – chasms – in the regulatory system. Some institutions were not regulated, some were regulated inadequately, and there was a lack of information available to the Government. There was insufficient planning for the failure of a major financial institution.

The need for regulatory reform understandably became the highest priority. Three factors appear to have increased the intensity of the Government’s response: widespread anger at financial institutions, some real, some politically convenient; the financial services industry’s self-inflicted wounds; and the requirement to trade-off a less risky financial system with its continued ability to support the economy.

The outcome has been a bias in favour of risk-reduction. Most attention has focused on the US legislative response – The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank) – although there have been other key components: changes in supervisory approach, regulation and enforcement.

The new supervisory regime for financial institutions is more prescriptive, proscriptive and intrusive, but also less flexible and predictable. Capital standards are being sharply raised, liquidity requirements are being imposed, and supervisory examinations are more frequent and more extensive. Supervisory examination ratings are also being widely reduced.

September 2010 saw new capitalisation and liquidity requirements adopted through the Basel Committee on Supervision, referred to as Basel III. As a result, banks will have to maintain a Tier 1 common ratio of 7%. The immediate response – but incorrect – of many in the market was to shrug this off as no big deal. I think however that we may see a number of banks face a significant capital deficiency under these new standards, which in practice must be higher than the published requirements. Both Basel III and Dodd-Frank provide that systemically significant institutions – all the major banks – have a surcharge above the basic requirement. Nobody yet knows what this will be exactly but banks will also need to meet market expectations, examiner expectations, and the unexpected.

Over the past decade, US banks have typically maintained capital ratios 150bp above regulatory requirements.Some market observers have sought comfort in the very long transition period before Basel III takes effect, partially in 2014 and fully by 2019. It is likely however that countries will shorten this substantially either formally or informally – limiting dividends, expansion and/or compensation levels unless there is full compliance.

The focus on capital may also have obscured the importance of the Basel III’s new liquidity requirements – against which reliable estimates state that the US banking system as a whole has a $1.1 trillion shortfall.

We are also now seeing a much more aggressive enforcement approach by regulatory agencies and law enforcement authorities don’t think it is an exaggeration to call the enactment of the Dodd-Frank Act the most comprehensive and consequential financial services legislation ever enacted in the US. Its passing is not however the end of the process. A number of the most important aspects are not self-executing but require further implementing regulations. There are also hundreds of ambiguities in the language used that must be resolved by the regulators. Dodd-Frank imposes sharply higher requirements on financial institutions deemed systemically significant. Its “enhanced supervision” applies to all domestic bank holding companies with $50bn or more in assets while elements also apply to foreign bank operations in the US.

Significant implications therefore arise in the way major banks operate, are structured and overseen. Fundamental however remains the need for more joined-up international regulation of financial institutions to avoid the “ringfencing” of banking activity along national lines and protectionist threats to the free flow of funds and global banking.

Rodgin Cohen is a partner and was the former Chairman of Sullivan & Cromwell from 2000 – 2009 and has served as its Senior Chairman since 2010. He is a leading US banking lawyer and played a central role in the US Government’s response to the financial crisis.