Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica: Knowledge is power

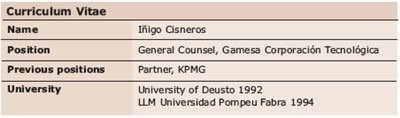

Iñigo Cisnero’s appointment as General Counsel of Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica coincided with a dramatic change in strategic direction for the wind energy company, he says. The result has been to place increased responsibility on the legal department, for its lawyers to play a much closer role in operations, and for them to be able to measure their success.

Iñigo Cisneros admits that on his arrival at energy company Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica he initially questioned the wisdom of becoming General Counsel. But he is also aware that his role in the company has expanded more quickly than was expected.

El nombramiento de Iñigo Cisneros como Director Jurídico de Gamesa Corporación Tecnológica coincidió con un nuevo consejero delegado y una radical reestructuración y reorientación de las operaciones de la empresa. El éxito ulterior y la expansión mundial de Gamesa han influido en el papel aún más relevante del departamento jurídico, y en la importancia respecto a la consecución de resultados. La introducción por parte de Cisneros de los indicadores de rendimiento (KPI) ha permitido al departamento jurídico poder demostrar sus capacidades, la eficacia y el valor que añaden a las operaciones del Grupo Gamesa en su conjunto.

“I joined Gamesa at what was a transitional time. I had been recruited by one CEO to discover when I arrived that a new one had been appointed, and who intended to embark on a restructuring and refocusing of the company’s operations.”

The General Counsel role as a result has become broader, more strategic, and significantly more involved with the company’s operations than Cisneros might have anticipated. The legal team, along with the company, has also grown substantially and now includes over 30 lawyers across three continents.

Changing times

Cisneros joined Gamesa in late 2005 having previously been a partner with KPMG in Barcelona. Until this time the company’s focus was on the development of new technologies in the aeronautics, wind and solar energy sectors.

The appointment of new CEO Guillermo Ulacia marked however a change of strategic direction, Gamesa’s core business is now the manufacture, supply and servicing of wind turbines and the development and sale of wind farms. The company is already the leading wind energy player in Spain and among the leading wind turbine manufacturers in the world.

Such change has inevitably impacted on the demands placed on its lawyers, says Cisneros. “When I arrived the legal department of Gamesa Corporación Technológia comprised a General Counsel and two other lawyers and, in line with the acquisitive nature of Gamesa until this point, their role was largely confined to M&A and corporate governance issues in support of the company secretary. The legal departments of other companies within the Gamesa group comprised in addition up to 12 other lawyers.”

The General Counsel was not therefore expected to have direct input into the day-today flow of the company’s operations. This however changed in the summer of 2006 when Ulacia’s new vision began to take shape.

Gamesa is now split into two main business divisions, the design, manufacture and sale, installation and servicing of wind turbines, and the promotion, construction and sale of wind farms. In addition, says Cisneros, a central corporate function has been created, with overall responsibility for strategy and corporate affairs, human resources and legal issues, abandoning the previous structure of different legal departments of Gamesa group companies one company-one legal department.

“The outcome has been that the legal team’s work is split along divisional lines with lawyers located within each, and a separate team handling all corporate housekeeping and transactional matters.”

Closer understanding

The international expansion of Gamesa has meant that the legal department now extends well beyond Spain to follow its growing manufacturing operations. The company has over 20 lawyers in Europe, a further six in the US and two in China. “The legal department now has a much closer interaction with the day-to-day company’s operations and decision-making,” says Cisneros

Cisneros believes that it is important for the legal team to have a full understanding of the company structure and its products if they are to add value.

“Perhaps it was a result of having spent my career within a law firm, but I saw a need to have control of all the real and potential legal issues we might face. But this is not possible unless you fully understand what we do as a company, what we want to achieve, and how our products are developed and manufactured.”

The start of the decade saw Gamesa on the acquisition trail as it sought to bring together the expertise and capacity to design, build and sell wind turbines under a single roof.

“At the end of the day we are producing wind turbine generators, which we have tremendous experience in, and the creation of individual wind farm businesses. This generates a lot of contract, supply and M&A issues but the key issues surround their innovative nature and the warranties and liabilities that are required to cover their manufacture and supply.”

Gamesa’s established line of GXmodel turbines accounted for 78% of the firm’s total €3.27bn revenue in 2007. Its wind farm business generated around 17% of total sales and the now discontinued solar business 5% – February saw the sale of Gamesa Solar to US private equity house First Reserve for €261m.

Comfort

Cisneros has ensured that guidelines are in place to determine the types of issue that the legal team regularly retains in-house and what work is outsourced to external law firms.

“The legal department focuses its role on the business critical areas and outsources specialist areas (where we do not have the requisite expertise) minimising the exposure to legal work. Among the areas that the legal team prefers to outsource are litigation and labour issues and those that surround the location of new wind projects.”

An important aspect of the legal teams’ work in recent years, he says, has been to standardise the terms and agreements that Gamesa enters into.

“On the commercial side much of the work is now template-driven enabling the businesses to be much more involved in matters. But in the technology division, for example, where there are obviously sensitivities around research and development, we still manage all nondisclosure, transfer technology and supplier issues.”

The sale of wind farm developments is comparable to that of a business unit, says Cisneros and due to our expertise, also usually managed in-house.

“There is often a lot of work resulting from land rights and usage and the need for administrative and local authority authorisations. These are inevitably specific to the location and where it helps to draw on good local knowledge,” he says.

Cisneros’s preference in such cases is to use small local firms, who understand the local cultural issues, have relations with the relevant authorities and are better able to communicate directly with land owners.

An adequate management of external counsel enables the in-house legal team to concentrate on matters in which it can clearly add value, he says. Indicative is the €6.3 billion turbine supply contract with Iberdrola Renewables – the second-largest supply contract ever in the wind power industry – intended for its wind developments across Europe, the US and Mexico between 2010 and 2012, which was signed in 2008.

The agreement was handled on the Gamesa side in-house, which predicts a strategic relationship to jointly develop wind projects across Europe, and the acquisition by Iberdrola of Gamesa’s wind projects in the UK, Mexico and the Dominican Republic.

“Most of our lawyers have backgrounds in large law firms and are therefore not only very capable but like to be involved with the company’s most important issues,” he says.

Cisneros accepts that it is not always viable to advise on issues or in markets in which the legal team lacks direct experience or where they require more manpower. Gamesa has recently embarked on a number of transactions in the US where it is now using external counsel. The In-house legal team controls the budget regarding the relationship with all external counsel.

“When we feel the need for extra support we like to work with firms with which we have previous experience, but for each transaction we will always send out a specific request for proposal (RFP) and initiate a competitive tender rather than relying on our traditional law providers to getting in this way the most of the market.”

Performance indicators

Cisneros believes that it is increasingly important to be able to demonstrate the value of the work being undertaken by an in-house legal team, in order to help raise morale and to benchmark performance.

“Our CEO’s view on performance is that ‘if you cannot measure it, you cannot improve it’. But while this can apply to many aspects of our work there is an understanding that much of what the legal department does is clearly affected by factors beyond our control.”

Cisneros has nonetheless developed a series of key performance indicators (KPIs) focusing on issues that can be controlled – for example, speed and accuracy of response, collecting and collating data, and meeting transaction deadlines.

“To define our objectives we had to understand our role, which is to operate like a professional services firm within the company. So it is important that we have strong relationships with our clients – managers within the different business areas – and that we react promptly to them. But we also need to understand that our key asset is our intellectual capital which we also have to grow.”

Cisneros surveyed legal business managers in order to help assess and establish performance indicators. But as well as understanding how his team was perceived internally, the exercise also, he believes, helped him to recognise service or knowledge gaps.

“What became apparent was a desire for the legal team to become more closely involved in the day-to-day business, to have an input on decisions and to pre-empt issues before they arose.”

One outcome is that the heads of the different legal teams now sit on some of the business division management committees, have a stronger sense of identity with the company and are closer to the client. But the process has also helped the further development of lawyers’ skills and to objectively set remuneration schemes, says Cisneros.

“There is now a sense of being more involved in company operations and of adding more value. The legal team has a higher visibility and those lawyers with specific responsibility can benefit from the glory when they are a success.”

KPIs have also helped to improve some of the process in areas in which the legal team routinely uses outside counsel, such as litigation, he says. “We use a lot of firms in different locations but our KPIs have helped to standardise the way in which matters are handled and to ensure that all the firms we use adopt a uniform response to recurring issues.”

Looking ahead, Cisneros sees new issues arising for Gamesa as it expands into new markets but also new opportunities. In March 2008, the company’s Fairless Hills, Pennsylvania, factory enjoyed a visit from Barack Obama while on the Presidential campaign trail highlighting his commitment to increased renewable energy use in the US.

Cisneros is though now placing increased emphasis on his team to take ownership of new projects and to co-ordinate the company’s response to these winds of change. “Senior lawyers will take more managerial responsibility and delegate more to the junior lawyers within the teams who in turn will learn more about Gamesa’s business.”

Cisneros is clear that company lawyers cannot be of real value if they are only ever reacting to issues as they arise. “Although this has been my first experience as a General Counsel role I have already learnt that it is not now necessary for me to control every detail of the work undertaken at Gamesa. I would rather build a solid legal team in which everyone has a clear role and responds to it”